Aesop’s Fables

This page is currently under construction. Please enjoy the critical introduction to the collection, as well as some PDFs, and check back soon for full access to the CAIRN metadata.

Aesop’s Fables are attributed to Aesop, believed to have been a slave in ancient Greece during the 5th century BCE. A master storyteller, Aesop used succinct tales to convey great truths. Best known for his anthropomorphized beasts and the morals they encapsule, modern-day society is still indebted to the writer. Ubiquitous expressions like “sour grapes” and “honesty is the best policy,” for instance, are attributed to Aesop’s “The Fox and the Grapes” and “Mercury and the Woodsman.” Aesop belongs to a larger tradition of thinkers and writers who read nature as a book and derived from it moral lessons and guidance on what a good life entailed.

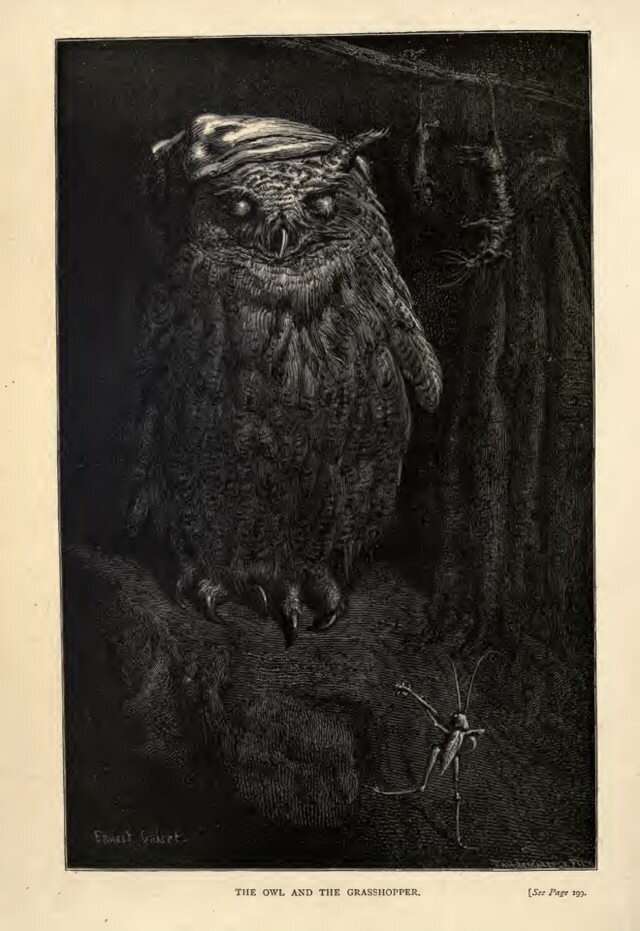

Aesop’s stories have inspired hundreds of visual interpretations, as the animals and their memorable lessons lend themselves remarkably well to artistic depiction. Artists underline aspects they believe to be most relevant to the story and bring new life to the centuries-old fable tradition. Ernest Griset’s illustrations in the Cassel, Petter, and Galpin 1869 edition, for instance, use clothing to highlight the anthropomorphizing of the animals. His choice makes the moral connotations of the fables stronger. In his rendering of “The Wolf and the Lamb,” the wolf, in search of justification for devouring an innocent lamb, is dressed as a dangerous grifter, evoking connotations of a cunning, treacherous evil. The lamb’s helplessness and innocence are in turn aided by its shepherd garments. These characterizations also evoke the dangers that urbanization portended in the nineteenth century. A similar effect is achieved with the Owl’s sleep cap, inspired by “The Owl and the Grasshopper.”

In Charles Robinson’s 1895 I.M. Dent & Co drawings, moral superiority is partly conveyed by stature. His interpretation of “The Fox and the Stork” demonstrates the stork’s moral high ground with her size, which overshadows the fox’s tiny, cunning presence. Finally, images like the ones prepared by Harrison Weir and J. Greenaway seen in the 1882 Belford, Clarke & Co. edition, such as “The Wolf and the Crane,” are impactful because of the plausible contortion of the animal’s bodies. The illustration serves an mnemonic devices to help the story —and its moral lesson— stay with the reader long after the book is closed.